Editing the three volumes of The History of Rancho Soquel Augmentation by Ronald G. Powell has been an unexpected journey for me that has had some major highs and major lows. As I wrap up editing the third and final volume of the series, Powell did what he has often done to me over the past three years and thrown a curve ball. In this instance, it has to do with the history of the Molino Timber Company, which ran splitstuff between the headwaters of Hinckley Creek and Molino Station from 1911 until 1918.

First: the revelations. Perhaps the most important thing Powell made me realize is that the Southern Pacific Railroad station known as Molino was not, in fact, the same thing as the Molino of the 1880s. That earlier Molino was an unofficial station that catered primarily to Timothy Hopkins’ splitstuff operation along Aptos Creek between the boundary of Soquel Augmentation and what would later become the Loma Prieta Lumber Company’s primary mill. This informal station was never registered by Southern Pacific and only went by the name Molino Junction because it’s where the road diverged for the Molino shingle mill. The later Molino Timber Company would be named after this early operation and also lend its name to the actual, registered railroad station. This later creation, established in 1911, was built at a site formerly known as Schillings’ Camp, which today is the Porter Family Picnic Area. In other words, I had the two conflated all along.

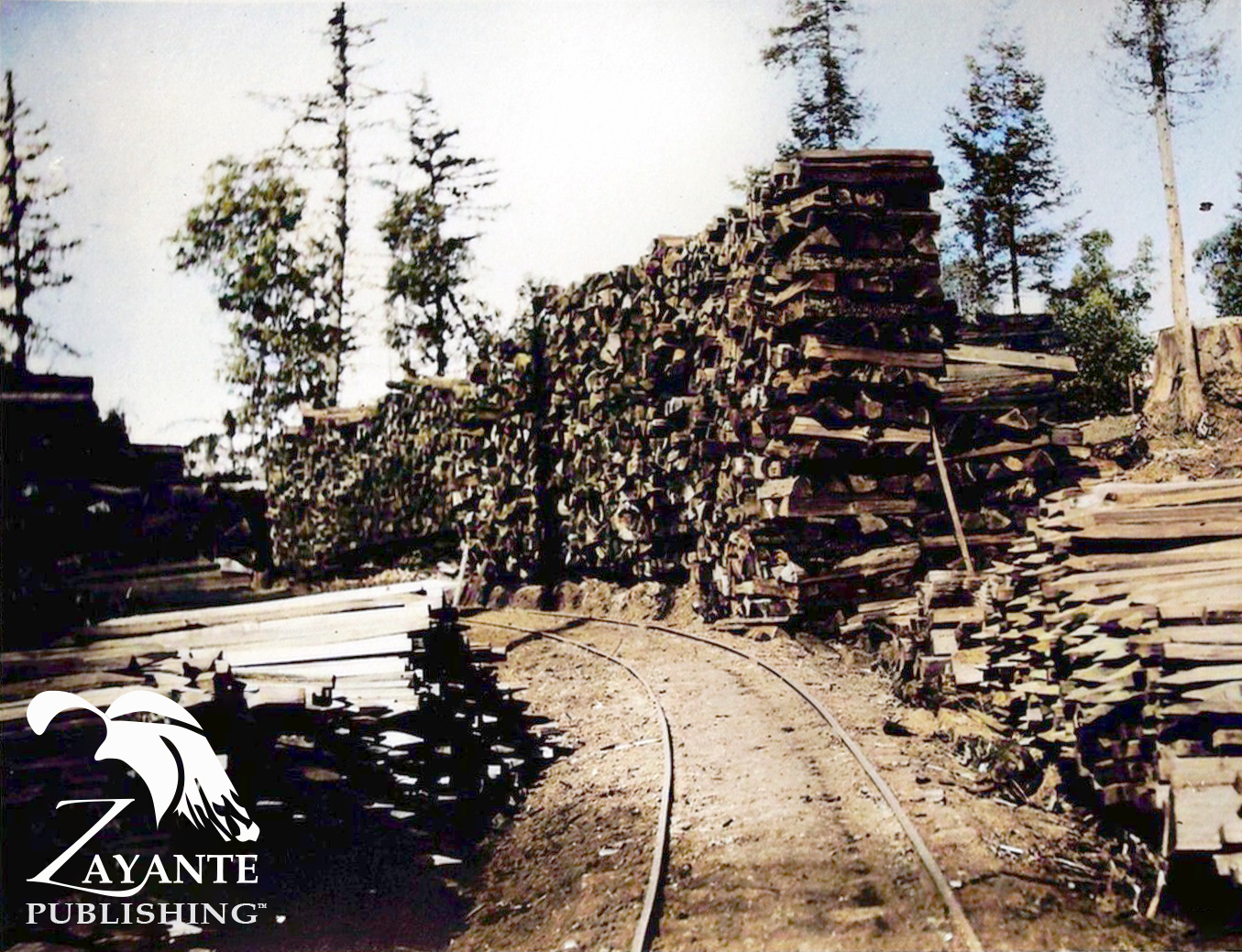

Piles of splitstuff on China Ridge, ca 1914. Photo by Bert Stoodley. Woods Mattingley Collection, Aptos History Museum.

The other major revelation is the relationship between the Molino Timber Company, Loma Prieta Lumber Company, Timothy Hopkins, and the F. A. Hihn Company/Valencia–Hihn Company. Essentially, from almost the beginning Molino ran as a subsidiary of Loma Prieta, which was under the near-exclusive control of Hopkins. Yet, Molino still was legally independent and negotiated early on a contract with the Hihn Company regarding splitstuff cut at the headwaters of Bridge Creek. Always eager to make some easy money, Molino contracted with the Hihn Company to transport the Bridge Creek splitstuff to Molino, where Southern Pacific trains could carry it to the various Hihn lumberyards in the area. It provided Molino with a nice, steady side income while it did its own splitstuff cutting on Hinckley Creek. But the scale of the splitstuff operation on Bridge Creek was incredible! The Hihn Company built a full railroad system and shipped in its old Betsy Jane saddletank locomotive. It operated along the creek for around seven years before getting buried in a landslide during a storm.

Where Powell really dropped the ball was regarding the chronology. The history of the Molino Timber Company is well reported by several lumbermen who were interviewed by various UCSC staff members and students in the 1960s and 1970s, most notably of whom was Alberetto “Bert” Stoodley, who served as Molino’s secretary for all of its existence. None of these men, however, gave dates in their recounts, forcing Powell to attempt his own calculations. Somewhere in the process, he strayed dramatically from logic and made several incorrect judgements that had a domino effect on events going forward. I only began to realize the gravity of his mistakes halfway through editing the section—and it required a lot of rewriting to begin with—so it took me two days just to recalculate the timeline so that it made logical sense.

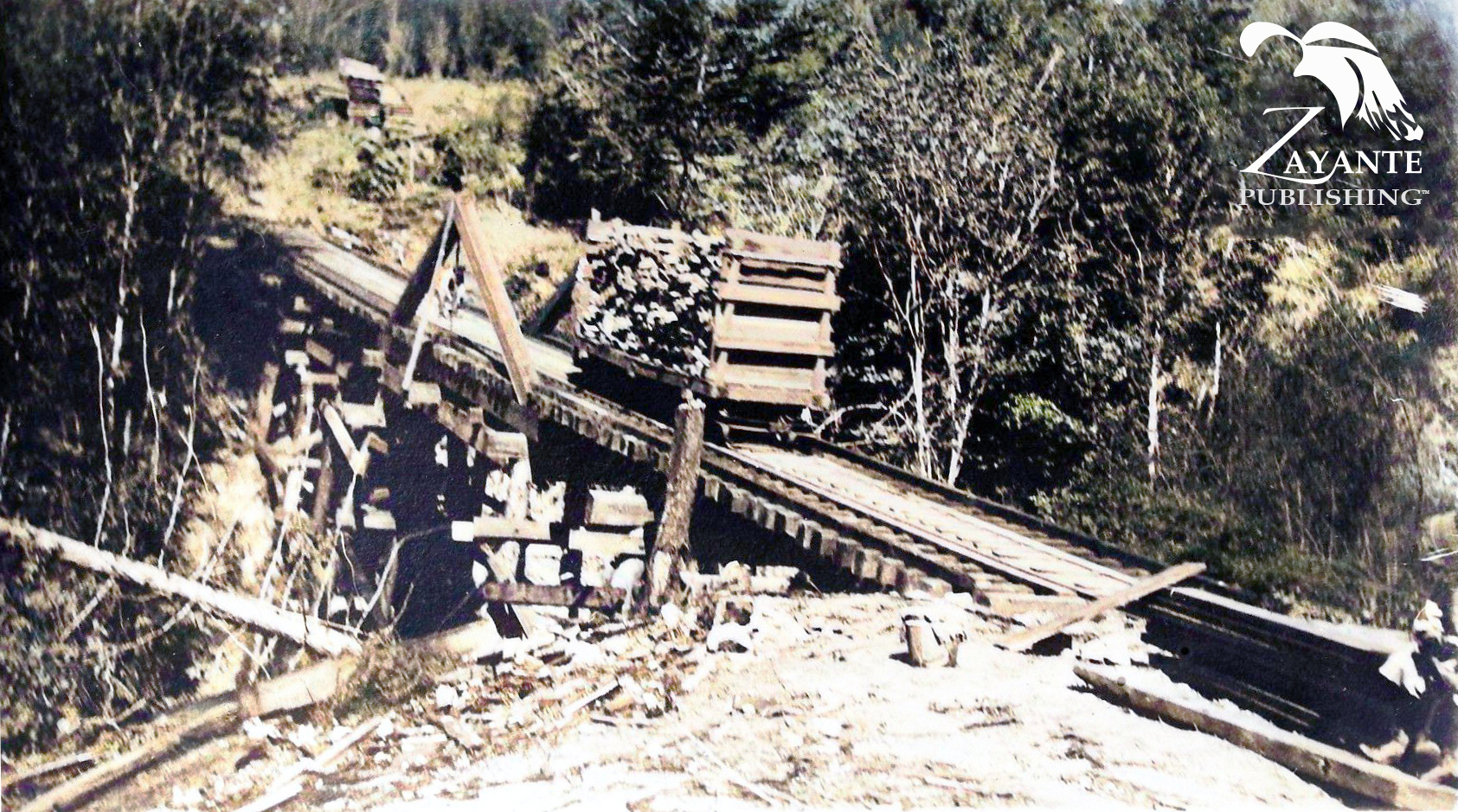

Molino Railroad grade beyond Camp 1, ca 1915. Photo by Bert Stoodley. Woods Mattingley Collection, Aptos History Museum.

What is clear is that there are only a few confirmed dates in the timeline of the Molino Timber Company’s operations in the Augmentation. Those are:

1910, May 31: The Molino Timber Company is incorporated

1915, Spring: Bert Stoodley disassembles old Loma Prieta millpond on Aptos Creek

1917, August 4: Valencia–Hihn sells Bridge Creek property to Loma Prieta

1918, September 11-12: Storm rips through the Aptos Forest, destroying Loma Prieta’s infrastructure throughout Bridge Creek

1919, December 1: Molino Timber Company dissolves

1922, June 30: Loma Prieta mortgages Augmentation property to bank

These, however, provided me with enough markers to correct Powell’s timeline. The event that triggered my reassessment was the permanent failure of a major highline cable rig that ran across Hinckley Gulch. This rig brought pallets of splitstuff from a landing beside Hinckley Creek to a landing near Camp 3, where it was then loaded onto Molino’s train and sent south to the Incline and beyond. Powell dated the failure of this mechanism to spring 1917, but he was not positive about that date and other circumstances made this timing very unlikely. However, he had based several other things off of his 1917 date, so I had to reassess all of his estimates.

To jump back to 1910, shortly after Molino was incorporated, it began producing splitstuff in the Augmentation under contract with Loma Prieta. It was only at the end of the year that it proposed building its railroad along China Ridge. But it took months of negotiating, buying building materials, grading, etc., to actually build this railroad, including the Incline, so by the end of 1911, the route only reached the top of the Incline where a newly-purchased Shay locomotive sat out the winter in a shed.

A flatcar of splitstuff at the bottom of the incline, ca 1914. Photo by Bert Stoodley. Woods Mattingley Collection, Aptos History Museum.

The next year was spent building the line to Sand Point, where Molino had entered into a contract with the F. A. Hihn Company to ship out splitstuff from the headwaters of Bridge Creek. Reaching Sand Point as soon as possible was Molino’s number one priority for 1912, and the job was accomplished by mid-summer. Thus, it was only in late 1912 or early 1913 that the track was extended to Camp 2 above Hinckley Gulch. Stoodley’s interview states that Molino remained at Camp 2 for two seasons, which means they extended the line to Camp 3 in late 1914 or early 1915.

This brings us to our second confirmed date: the dismantling of the old millpond. If Loma Prieta had any notion of its future plans, it would not have allowed the dismantling of the old pond in spring 1915. After Frederick Hihn’s death in 1913, several lawsuits were fought over his estate. In July 1916, the A. M. Elam Company cruised the Hihn Company’s land which led to a provisional agreement in the fall between the company and Loma Prieta whereby the latter would eventually buy the former’s Bridge Creek property once the lawsuits were settled. As a result, in early 1917, Loma Prieta finally began making moves to return to the Augmentation.

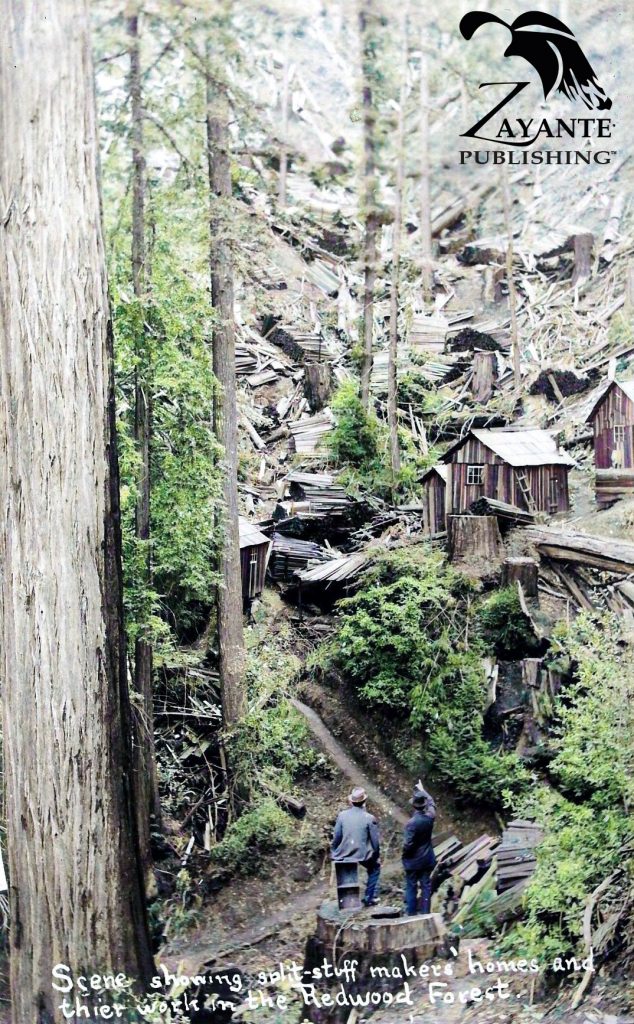

Piles of splitstuff near Camp 3, ca 1915. Photo by Bert Stoodley. Woods Mattingley Collection, Aptos History Museum.

Molino’s accident, therefore, must have happened sometime in 1916. This would have allowed the company to reassess its options, test various alternative methods of bringing splitstuff to the railroad line, and conclude that their enterprise had reached its end. Assuming this all took time to do, the company probably only gave up on Hinckley Gulch at the end of the 1916 season, by which point Loma Prieta was fully aware of the problems Molino faced. The purchase of the Bridge Creek property, therefore, may have been partially to prop up the Molino operation.

In 1917, Molino extended its line further to and around the headwaters of Hinckley Creek. This was partially done so splitstuff could be loaded directly onto flatcars, and partially so larger logs could be loaded and sent to a small holding pond north of Sand Point. At the same time, Loma Prieta had begun rebuilding its mill on Aptos Creek and once more dammed the creek. In August 1917, the company finally acquired the Bridge Creek property and could begin harvesting timber in the former Valencia–Hihn land. They immediately took over operations in the splitstuff grounds at the headwaters of Bridge Creek and resumed sending those up to Sand Point.

Loma Prieta decided in late 1917 or early 1918 that it wanted a railroad to go up Bridge Creek, which meant it needed Molino’s rails. It bought its own Shay locomotive but instructed Molino to cut back its railroad line to Camp 2. By this point, Molino was barely its own corporate entity. The two miles of track removed from the China Ridge line were installed along Bridge Creek, with plans to ultimately extend the track into the splitstuff area and abandon the China Ridge railroad entirely. Molino even began sending logs down into the area in anticipation that they would later be sent down the railroad to the mill. This route included today’s log bridge and had its center at Camp 4, just north of the bridge. Unfortunately, all of this was destroyed, including the splitstuff area, in the September 1918 storm.

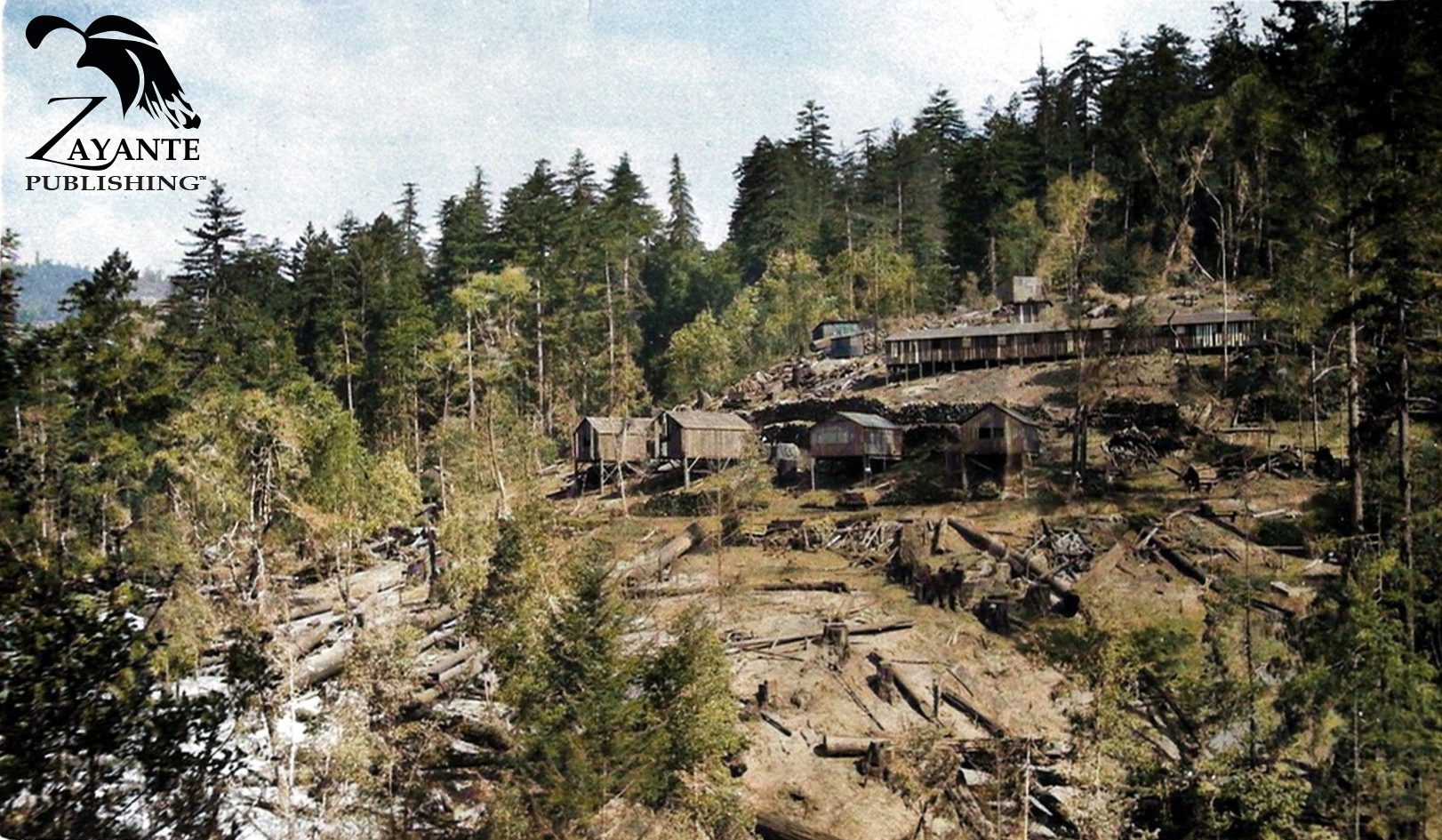

Hoffman’s Camp—Loma Prieta Camp 5, ca 1920. Photo by Bert Stoodley. Woods Mattingley Collection, Aptos History Museum.

It was only after this storm that Loma Prieta decided to build a new line farther up the hillside, eventually passing through Camp 5 (Hoffman’s Historic Site) to Big Tree Gulch. Powell inexplicably believed that both the lower and upper lines operated simultaneously. What is fairly certain is that the China Ridge railroad was dismantled in early 1919 and Molino’s Shay lowered in spring, so that it could be used on the Big Tree Gulch line. With the splitstuff area destroyed, there was no longer a point in maintaining the expensive ridgetop railroad. Loma Prieta may have hoped once more to extend the Big Tree Gulch line to the abandoned area, but it never happened. Meanwhile, Molino dissolved at the end of the year.

For about two seasons, though split unevenly across three summers, Loma Prieta harvested the rest of the timber in Bridge Creek, though it never was able to complete the job in the splitstuff area. At the end of 1920, the Aptos Creek mill was permanently shut down and all logs that needed cutting were sent to the San Vicente Lumber Company’s mill on the west side of Santa Cruz. The narrow-gauge tracks were all removed in 1922 and then Loma Prieta’s property was mortgaged to the People’s Savings Bank of Santa Cruz until it could pay off its debts.

Logs heading into the Loma Prieta Mill from Bridge Creek, ca 1920. Photo by Bert Stoodley. Woods Mattingley Collection, Aptos History Museum.

Powell made several oversights in his telling, misdating the extension of the track to Sand Point in 1912, pushing the date of the failed mechanism to 1917, and believing that both the Bridge Creek and Big Tree Gulch railroads were built simultaneously, despite there being a lack of available rail for both routes. He also suggested that Loma Prieta planned its grand return in 1915, which the demolition of the millpond is factored into the equation.

It took me a lot of time and energy—and two long weekends of writing and rewriting—to properly organize and intercut this story throughout Chapters 3 and 4, but I am very happy with the results. Hopefully you all will be too! The Shadow of Loma Prieta: Part Three of the History of Rancho Soquel Augmentation by Ronald G. Powell will release Fall 2022 and be available at Bookshop Santa Cruz and on Amazon.com. Stay tuned for a press release in the coming months.